Display board 8

THE DYE-WORKS

Silk was a luxury product, destined for an elite market, closely tied to the evolution of fashion. In this context the colour and dyeing were of utmost importance. In fact, the most highly prized elements of a consignment of silk were its brightness and the permanence of its colour, which contributed decisively to determining its economic value.

In 1766 there were 5 dye-works in Rovereto employing in all 80 workers. The quality of the silks, dyed in Rovereto in vivid colours, was admired all over Europe. The high grade of the dyeing process was guaranteed by the purity of the waters of the river Leno, the quality of the raw materials used and the technical skills attained by the workforce. In the 1770s the revenue from this activity equalled 40% of the production of the yarn, even if the cost of the raw materials in this sector impinged strongly on the return.

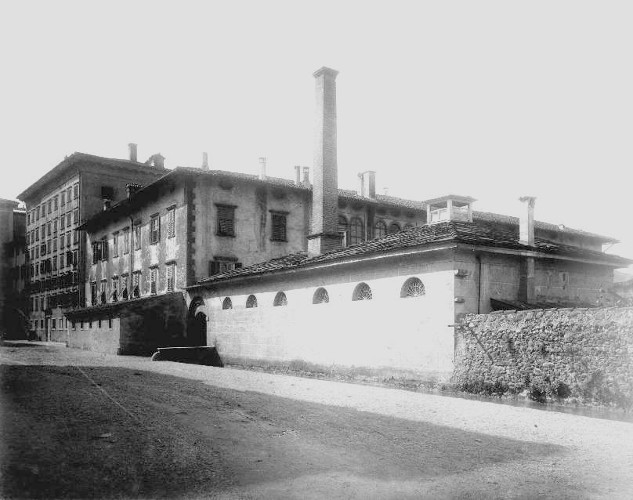

Some buildings that once functioned as dyeworks, can be recognised in the town centre. The Bridi dye-works were particularly important, located in the ancient via delle Ghiaie, now via Bridi, next to the low building which housed the mill of the same name. The broad balconies on the second and third floors overlooking Piazza Suffragio, were used to hang out themdyed silk to dry. Another leading dyeworks belonged to the Masotti family in via Tartarotti, in the building which housed the Land Registry offices and the Land Register. Here the large loggia on the second floor was occupied by drying racks for the silk.

At the beginning of the C 19th progress in the chemical industry and the discovery of artificial dyes led to a crisis in Rovereto's dyeworks: their rapid disappearance forecast the irreversible decline of the entire silk industry.

THE ALCHEMY OF COLOUR

A "recipe" for every shade of colour, using pigments and fixatives of natural origin, was arrived at on an empirical basis The ingredients came from all over the world and the complex operations involved in preparing the colours were handed down from generation to generation of master dyers.

The lichen, used for obtaining violet came from Madagascar, the safflower for reds and roseate fromEgypt, the floating grass for black from Istria, the wode for blue and iris for green from the PreAlps. The best indigo was the one from Guatemala, followed by the one from Armenia and the one from Santo Domingo. The rock alum, a fixative, came from Civitavecchia. The various kinds of wood from which dyes could be made came from definite different parts of South America, generically defined by the name "Spanish". The lemon juice required to fix the dyes was produced in Sicily. The most expensive of all the materials used in the dye-works was the orellana dye used to make an orange-yellow colour, derived from a Brazilian plant cured in Marseilles. The fenugreek, liquorice roots and rubia were acquired from Greece. Soap, a substance much used in dyeworks, was made in Venice.

From this rapid overview of the dyer's art, it becomes clear how extremely complex the activity was and how its workers needed uncommon skills and know-how. It also becomes evident how those operating in this sector needed to establish relationships with the most important market-places in Europe and the principal ports of the old continent, like Lisbon, Antwerp, Marseilles and Genoa. Via these intermediary ports trade relations spread out to Asia and the Americas.