Display board 4

CULTIVATION OF THE MULBERRY

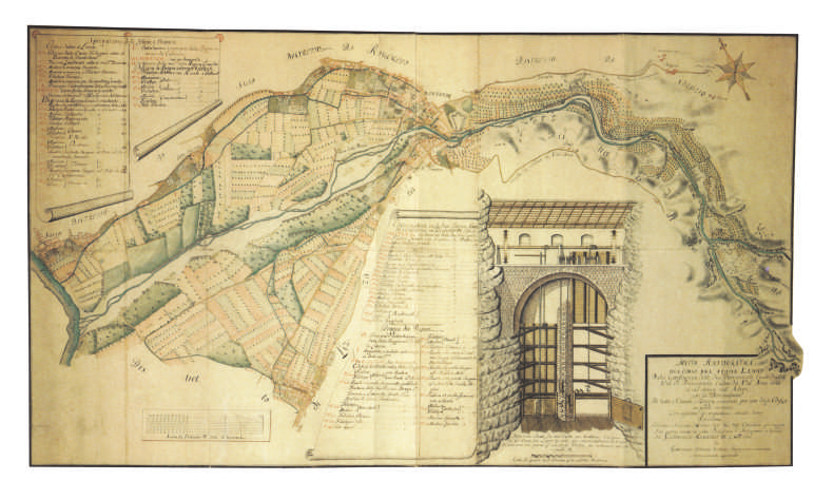

Mulberry trees, also known by the dialect term "morari", appeared for the first time in the municipal records of Rovereto in 1524, when it was established that these trees should be planted ten feet from the boundary of neighbouring property. The trees had probably been introduced into the zone already some years previously, towards the end of the Venetian domination in 1509. Mulberry cultivation, fundamental for raising silkworms, progressively increased, in parallel with development of the silk industry, to the point of covering almost the whole of Trentino below 600-700 metres in the second half of the eighteenth century. The mulberry tree became one of the predominant features of the landscape, as Nicolò Cristani de Rallo wrote in his "Brief Description of the Municipality of Rovereto" in 1766. Similar impressions were registered by two travellers, the philosopher Montesquieu, who passed through the Vallagarina in 1729, and the intellectual, painter and engraver Frédéric Bourgeois de Mercey on a journey through the Tyrol and northern Italy in 1830.

"The whole countryside, Venetian and that of Trentino as far as Trento is full of mulberries, which grow even up on the rocks of Trentino. The mulberries grow wonderfully on the hills and in the valleys: the soil is extremely fertile. In the same field you can see many kinds of cereals, vines climbing over cherry trees, elms, ash, walnuts and mulberries everywhere."

MONTESQUIEU, 1729

Between Trento and Rovereto "what saddens this fascinating countryside is the absolute bareness of the mulberry trees along the roadsides, denuded of their leaves which feed the silkworms (…) As one nears Rovereto the vegetation becomes richer: quinces, pear and apple trees, mulberries all joined together by dense garlands of vines, that seem to be battling for the terrain, making the valley into just a great orchard."

F. MERCEY, 1830

THE EVOLUTION OF RURAL BUILDINGS

Besides shaping the landscape with the widespread distribution of mulberries throughout the area, the sericulture and silk industry also had a profound influence on the evolution of the structure of rural buildings.

The peasant's house consisted of two large rooms with a barrel vault in masonry on the ground floor: one for sheltering the farm animals and the other for the inhabitants. The latter usually had a fireplace without a chimney, so the smoke filled the house and was emitted via two holes in the head wall. This room was used for eating, sleeping and doing winter chores, although during the summer months people slept in the hayloft.

With the arrival of the silkworm, this humble abode, entirely designed for defence against the winter cold, with little light and very damp, was transformed, since the silkworm can only live in a light, airy place.

Former dwellings were reorganized, enlarged and raised by one or two floors. Silkworm rearing required a lot of space: just consider that for every ounce (28.5 g) of eggs 50 square metres of space were necessary and each family bought between 3 and 6 ounces of "seeds".

The first floor was typically given over large kitchens, with wide spaces filled with timber frames for the larvae newly hatched in May when the temperature was still cool. Then the larvae in their final stage of growth were transferred to the upper floors and loft and the mountages, (called "bosco") that is that dense collection of branches where the silkworms would construct their cocoons.